Children of the KLA

18 years on from a war that destroyed most of the country, the children born around the time of the conflict are coming of age. They are working to rebuild, hoping to banish the ghosts of the past and live better than their parents ever did.

On June 11, 1999, the last major conflict of the Yugoslav Wars ended, as Serbian troops withdrew from Kosovo after a NATO bombing campaign and the United Nations took responsibility for the fledgeling state.

Once part of Yugoslavia, ethnic Albanian majority Kosovo sought to become a nation in its own right as the communist state collapsed. With a long history of ethnic tension and violence between them, the Serb-dominated government in Belgrade waged a brutal war to keep Kosovo a part of a rump Yugoslavia.

Prekaz, a small town 30 kilometres northwest of Kosovo’s capital, bears striking scars of the recent violence. Once home to the leaders of the Albanian resistance, the Kosovo Liberation Army, in 1995 Serb Special Forces attacked a compound on the edge of the village, belonging to rebel commander Adem Jashari, shelling the house for three days.

58 people were killed, including 18 women and 10 children, as well as the rebel commander and some comrades.

Held together by scaffolding, riddled with holes from bullets and mortars and untouched since the assault, the house is a haunting reminder of the cruelty of that war.

Enlarge

For many Kosovars, according to Vlera Hatemi, a 19 year old student at the University of Pristina, “it shows a great contribution and how the fighters idealised freedom and how much they contributed to our generation and future generations to live in a free and stable country.”

Vlera’s grandfather, Xhafer, who lived through the war, said over a million people fled the country, 15,000 were killed and almost 18,000 women were raped.

Enlarge

He sees hope for his grandchildren’s future, saying “there has been a lot of progress, especially females are some of the main contributors in building the country.”

Kosovo today is a nation seeing significant economic growth, and it has enormous potential, but also major problems.

Over 40 % of Kosovars are under 25 years old. The country has the youngest population in Europe, but the slow rebuilding of the economy after the war has limited opportunities for people to improve their lives. Unemployment remains stubbornly over 25%, and less than half of 15 to 25-year-olds are in work.

With average incomes below $4000 and no end in sight for the employment crisis, many young people in Kosovo feel there is little chance of their prospects at home improving.

It is politicians, and their parents’ generation, that young Kosovars blame for their bleak futures.

Some simply see politicians as corrupt; they say that they look after themselves rather than the country as a whole, finding opportunities for their families and friends, not for everyone. In 2015, a UN-backed poll found almost 3/4 Kosovars were dissatisfied with the state of government, percieving it as crooked and focussed on nepotism rather than making Kosovo better for everyone.

Others think those in power are doing what they can, but what they can simply isn’t good enough, with economic and political realities checking progress.

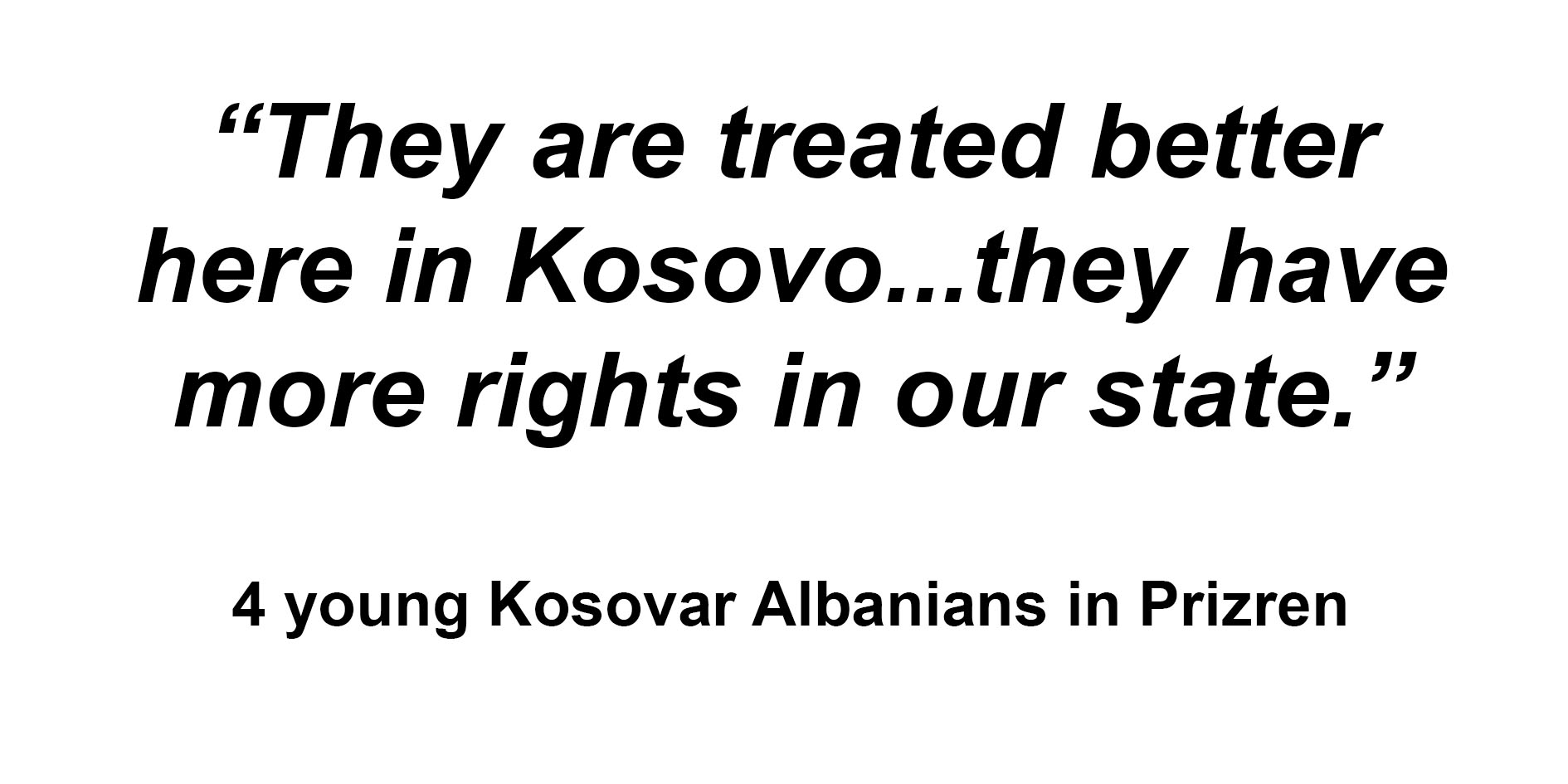

More concerning are the young people who blame the post-war settlement for their problems. Whether Serb or Albanian, these people see the “other side” as having the protection of the state, as having more rights, as not caring about their future.

At the same time, these young people express their desire to achieve a better collective future. These conflicting views show that the divisions that ripped Kosovo open 25 years ago have not yet healed – these are the divides that need to close for the country to truly move forward.

The lack of opportunities caused by continuing division, political and economic instability drives many young Kosovars abroad.

“The situation Kosovo now is, I need to leave”, said an 18-year-old law student, who was smoking a joint in an old fortress overlooking the pretty city of Prizren, in the south-west of the country.

Raki Ftoni and his three friends were frustrated with the lack of opportunity on offer to them in Kosovo. They say it has “ changed a lot in a better way” since NATO expelled the Serbian military in 1999, but it has also changed in “a bad way, in politics it is bad with a lot of corruption”.

Enlarge

Across the ethnic divide, many young Serbs echo these frustrations. Jakob & Drazeb from Mitrovica, a town with deep ethnic divisions in the north of the country, explained that they “want it to get better, but you have people who don’t want, you have people who have some profit of this kind of situation, like leader who controls our people.”

Both sets of young men say they are disadvantaged that the people across the divide get more money and help from the government, and foreign organisations working in Kosovo.

Before the camera was turned on. Raki joked about hating Serbs, and though he wasn’t being serious, there was enough bite to his comment to show some ethnic animosity remains.

The young Serbs of Mitrovica don’t feel comfortable spending time in the more developed Albanian part of town, said Jakob, saying “When you live here, you can expect some things to happen, you don’t know what, you don’t feel safe.”

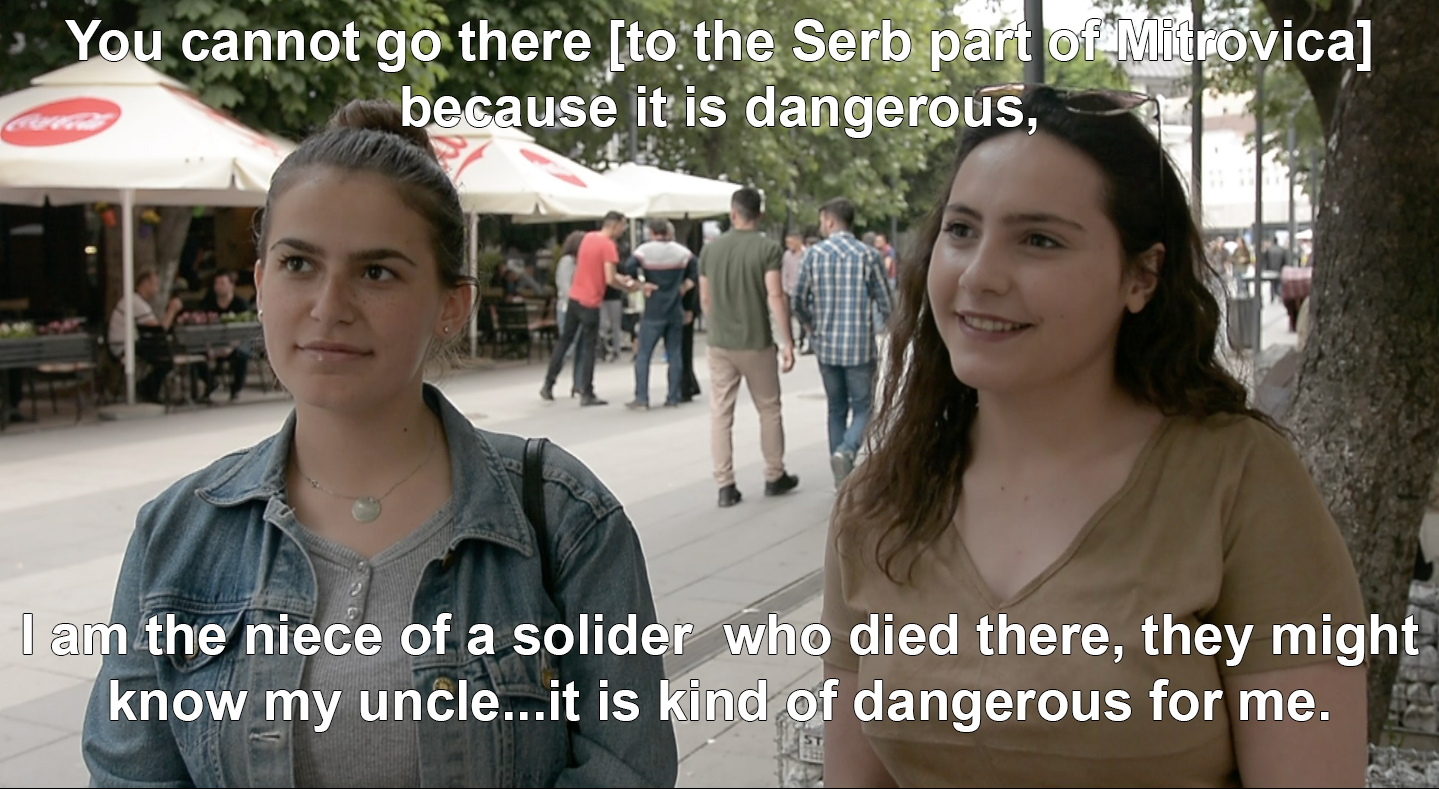

A pair of young Albanian-Kosovars, Diellza Beshiri and Renita Fejza, both 16, who were shopping in the bustling centre of the town expressed similar fears – that Serb areas aren’t safe – worries they picked up from their parents.

Seconds later, Diellza, who works in a café that serves the Serb community, said “I have a lot of contacts with people from the north because I work at Jaffa Place and half of our customers are from Serbia, from the other side, they’re actually quite friendly, they’re not aggressive.”

Instinctive division remains in Kosovo, tainted by the blood of close relations on both sides, but young people are looking to leave that in the past, even though they still have similar fears to their parents.

“I think that especially the younger generations define themselves as Kosovar citizens rather than by [ethnic] nationality”, argued Vlera in a modern espresso bar on a leafy street in the capital. From her experiences living in the capital, she’s found that her peers are overcoming ethnic tensions and are working together to try and improve their lives.

Even though the old divides run deeper in towns and cities outside the capital, young people away from Pristina to see that their best shot of enjoying better lives relies on the whole of Kosovo coming together to tackle the social and economic problems holding the nation back.

Enlarge

This ambition to rebuild and improve things for themselves and their communities after the destruction of the war and the 2004 country-wide violence has pushed tens of thousands of young people into higher education.

There are around 130,000 students enrolled in university across Kosovo who make up more than 6% of the population, with the country having almost twice as many students per head as the UK. This has created a glut of graduates, and some people are concerned the degrees are worth very little, with a 2015 investigation by the Balkan Insider labelling some Kosovar universities and “diploma mills.”

On top of this, there are thousands more young Kosovars who go to university in neighbouring countries, where they see a brighter futures than is on offer at home.

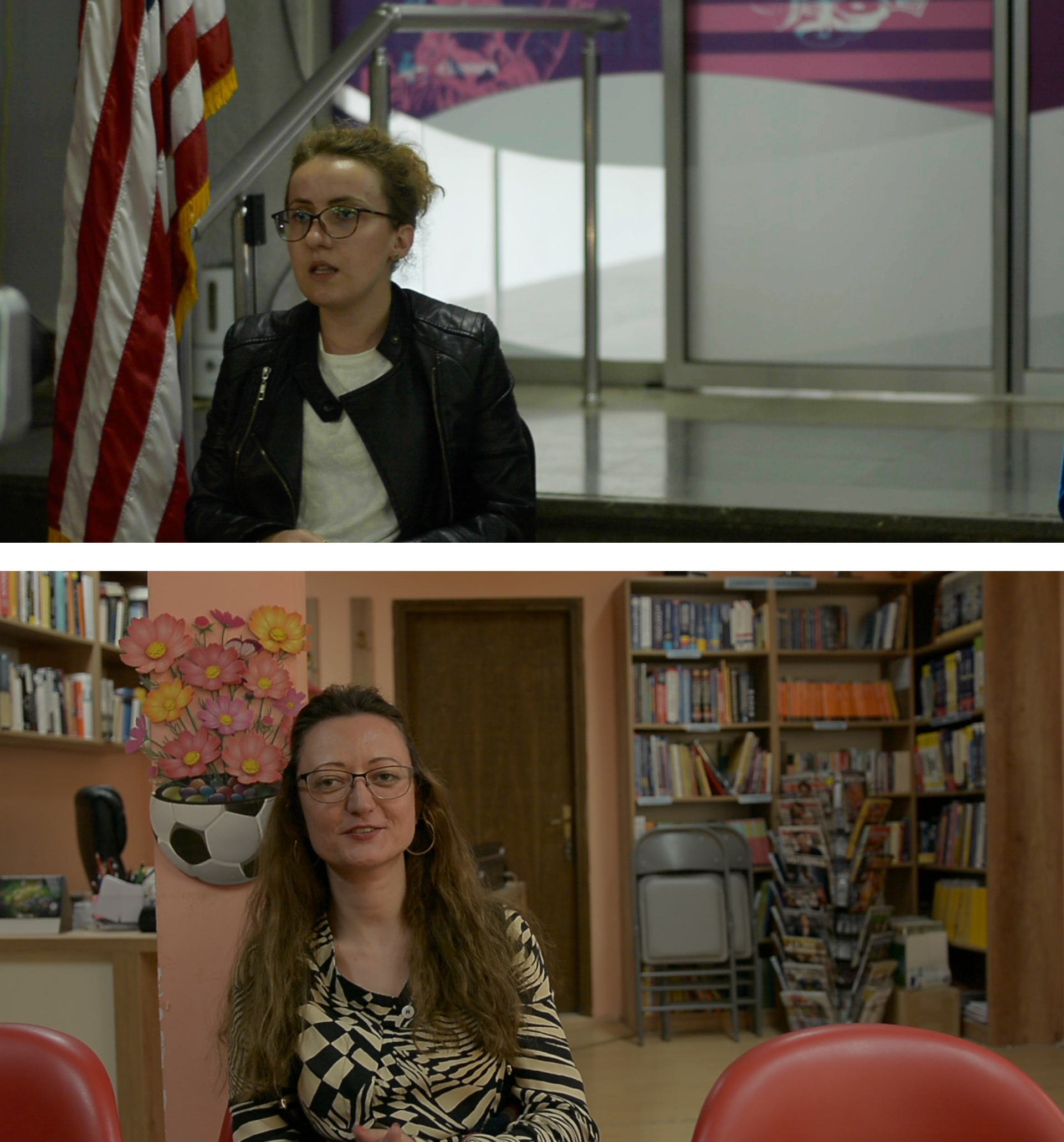

As part of the USA’s investment in rebuilding Kosovo after the war, they set up three American Corners in Mitrovica, Prizren and Pristina to provide space for people to access books in English as well as to help people learn the language.

Irena Otasevic, who is of Serbian descent, helps run the American Corner in Mitrovica. She said that the children and young people who make use of the centre are excited to learn English and to learn about Western culture.

Asked if the sessions the Corners run are getting more popular, Irena explained: “they indeed now are getting more and more popular, because students started to think it is a good opportunity for them.”

Learning English is a way out for many young Kosovars, Irena thinks, giving them the skills to work in Europe and the US. For others though, she says she believes that “young people can do more like they are doing to create a better future.”

Enlarge

One of the volunteers at the American Corner in the capital agreed. Gresa Bujupaj said how the young people there are looking to connect with the West and bring ideas from abroad into the country to help it progress. She said that “the youth will help, but I think it’s mainly like going out, studying abroad, bringing ideas here, developing the economy.”

Though the corner in Mitrovica serves mostly a Serb population, and the one in Pristina mostly Albanian youngsters, volunteers at both centres, as well the one in Prizren, say those who use the American Corners have similar goals.

Whether Serb or Albanian, they want to find out more about the West (in particular the USA), to relate to their Western peers and to get educated, either in Kosovo or abroad so they can gain the skills to find a better life and improve the lives of their communities.

At the American Corner in Pristina, Gresa thinks the influence of the West on younger people is leading to positive change in the country, “We’re a bit rebellious and I see it in all my friends, but rebellious in a good way, we are in contact with Western people and we’ve started thinking the way they do, going out more, and this helps.”.

The two young Serbs in Mitrovica told us they spent their spare time writing rock music, with bands like Metallica and Anthrax, rather than homegrown groups being their inspiration.

A love for American culture draws many the dozens of schoolchildren who visit the American Corner in Mitrovica to the centre. As well as the culture, Irena sees a lot of young people who are attracted to the Corner because: “there are a lot of programs they can go and study in the US that offers scholarships, and it is a great opportunity for them as well to see and experience a different life.”

The dream of a better life, and the willingness to leave Kosovo to find one was something all the young people interviewed for this article had in common. The lives of the Children of the KLA are defined by the reconstruction effort, which can limit opportunity.

Things have gotten better, but there’s a long way to go.

CKLA from Jake Hurfurt on Vimeo.

For Vlera, becoming a member of the EU is the best way to improve Kosovo, and she was adamant in claiming Kosovo can offer something to Europe as well.

“I truly believe in seeing Kosovo as part of the European Community…we have a lot to offer to Europe and vice versa, we have a very skilled labour force, natural resources and many other things that would enable us to have tighter cooperation between Kosovo and other EU countries.”

Though the country has signed an initial agreement with the EU, it lags behind its Balkan neighbours in talks with Brussels. Kosovars still need a visa to travel across EU borders, unlike other Balkan states.

As well as her studies, Vlera has interned at consulting firm Deloitte in Pristina. As part of her work, she looks at which areas NGOs and government should focus on for growth. With acres of lush countryside and the country’s first ski resort on the way, tourism will soon be a key sector in the economy. Exporting IT services and natural resources to Europe will also be important if the EU drops tariffs on goods and services from Kosovo soon.

Enlarge

Her grandfather was less optimistic about the future if Europe does open it’s doors to the country’s young people, “Unemployment is making very hard for youngsters to stay here in Kosovo, so that’s why most of the youngsters want visa liberalisation and moving to EU rather than staying here.”

For someone who has seen his country suffer through fascist rule during WW2, followed by communism and a war that has become a byword for violent sectarianism, Xhafer is still hopeful for his grandaughter’s generation.

“There has been a lot of progress, especially females are some of the main contributors in building the country.” Xhafer Hatemi

The children of KLA are ambitious, and even though many of them are seeking to leave the country. They are, with help from the West, rebuilding bridges across ethnic lines, to take their country into a brighter tomorrow.

Enlarge

Words – 2188

Credits & Bibliography:

Thanks to

Labinot Hadjari for arranging interviewees

Vlera Hatemi for sparing a day and a half, and her grandfather

American Corners in Pristina, Prizren and Mitrovica

All the other interviewees

STATS:

Kosovo Agency of Statistics (KAS) – University numbers, unemployment data

CIA World Factbook – demographic data

Eurostat – non-Kosovar European statistics

International Monetary Fund – economic data